A Cybernetic Revolt - The Story of Captain Power and the Soldiers of the Future

The future wasn’t just a title or a setting in time for Captain Power And The Soldiers Of The Future, it was also supposed to be the show’s destiny.

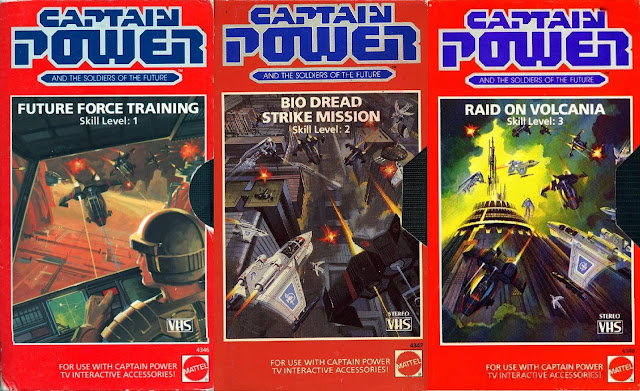

The program itself—an action- and CGI-laced science fiction drama intended to tackle weighty themes in sweeping, season-long arcs—aimed to evolve both the medium and the message of children’s television. Its merchandise tie-ins were supposed to revolutionize interactive entertainment and gaming (the instruction manuals for the play-along videotapes that came with toys like the PowerJet XT-7 actually began with the bold introduction, “Welcome to the future!”) A successful combination of all of those elements even had the potential to pioneer a more harmonious and mutually satisfying marriage between art and commerce.

The very genesis of the greater Captain Power concept came from the simple realization that no one had gone there before. In 1985, filmmaker and themed entertainment visionary Gary Goddard started playing around with the name because he thought it sounded cool. Pleasantly surprised to discover that no one else already owned it, he trademarked “Captain Power” for himself and immediately sat down at his typewriter to sketch out a cast of related characters and a bare-bones glimpse into their universe.

Goddard, who had previously collaborated with Mattel on He-Man And The Masters Of The Universe, took his new idea to the toy manufacturer. “We got this meeting and we said, ‘We think we have the next great thing,’” he recalls in Out Of The Ashes: The Making Of Captain Power And The Soldiers Of The Future, a documentary included as a special feature in the complete series box set released in 2011. “It was not interactive at this point. The big innovation was going to be that it’s a live-action show for kids with CGI robotic villains that our live-action guys are going to fight against.”

Mattel responded by showing Goddard and his team the interactive technology they’d been building that would allow children to aim and shoot at moving targets on television screens. With action figure sales declining, the company was hungry to launch its new offerings and thought that Captain Power would be the perfect platform for them. Goddard agreed, as long as the way in which the technology was incorporated into the episodes remained unobtrusive. In addition to a merchandising deal, Mattel went on to bankroll the entire production.

At Mattel’s request, the Captain Power crew set up shop in Toronto in the spring of 1987, filming the bulk of the episodes inside a hollowed-out bus depot in the city’s west end to take advantage of tax incentives and a low Canadian dollar. In its own way, even this scenario was the first of its kind, given that the Great White North’s development into a reliable source for science fiction TV productions was still a good decade away. (For Torontonians, the transformation of a public transit hub into a postapocalyptic wasteland holds its own prescience, given the current ailing state of the city’s bus, streetcar, and subway system.)

Stateside, Goddard focused on his main priority, the story, by enlisting a group of science fiction writers to flesh out his initial outline. Marc Scott Zicree developed the series bible. Future Babylon 5 and Sense8 creator J. Michael Straczynski was hired as a story editor. Along with Larry DiTillio, they would take on the bulk of the screenwriting duties, as well.

The world those men built was, arguably, Captain Power’s boldest risk of all. “It would have to be a big vision and a big world,” Zicree says in Out Of The Ashes. “And I was committed to the idea that this would be an adult show, that we would create it exactly as if it were an adult show. We wouldn’t condescend at all.”

On that point, the show creators most definitely succeeded. There’s not a hint of condescension, pandering, or simplification to be found in the final product, a 22-episode run that aired in syndication from September 1987 to March 1988.

Set in 2147, on what’s left of Earth (or “the legacy of the Metal Wars, where man fought machines—and machines won,” as the show’s exposition-heavy opening credits describes it), Captain Power And The Soldiers Of The Future pits its eponymous leader, the young Jonathan Power (Tim Dunigan), against an army of highly intelligent machines in the final stages of their plot for world domination.

Lord Dread (David Hemblen), the leader of the machines, operates out of a volcano base and leads a collection of remorseless digital killing machines called Bio-Dreads in a quest to wipe out, or “digitize,” human beings and leave the world to a purely mechanical race. Mankind’s only hope are Power and his Soldiers Of The Future, a rebel group of combatants and Dread traitors who are armed with little more than an abandoned North American Aerospace Defense Command mountain base, a handful of “power suits” (essentially unitards that morph into high-tech exoskeletons), and a fading memory of a better world.

With overt allusions to fascism and eugenics, Captain Power often unflinchingly tackled political themes, but its personal ones cut even deeper. For all its talk of the future, it was really a show about the past. Yesterday looms over the soldiers just as constantly—and almost as unsettlingly—as the Bio-Dreads who threaten their annihilation, demanding to be confronted and reconciled, learned from and lived with.

Most of the main characters are tested by their past in some way over the course of the season. Jonathan meets a former lover (played by lauded Canadian novelist and playwright Ann-Marie MacDonald) and clings to their shared history as she faces an uncertain future in the first episode, “Shattered.” Hawk’s (Peter MacNeil) resolve and his desire to keep fighting the good fight falter when he runs into an old flame of his own in “Wardogs.” Tank, the ground combat expert of the crew (Sven-Ole Thorsen, frequent co-star of Arnold Schwarzenegger), is sent into a self-searching tailspin when he runs into a man who came from the same genetic facility as him and worries that his current actions will never make up for the kind of person he used to be. Even Lord Dread’s favorite hench-machine, the cunning and haughty Soaron, appears to struggle with his origins in some way, betraying oddly philosophical mid-mission reflections like, “First there was darkness but now I think all the time. I fight and I think. I fly and I think. And I listen to the voice. And I find something in my program I do not understand. There is something in the dark…”

The influence of the past is always clear in character’s motives and often directly responsible for the life-changing decisions that soldiers and civilians make. A blind artist rejects Lord Dread’s vision-restoring technology when she sees what the machines have done to the world in “A Fire In The Dark,” choosing to live with her memories instead. “He offers me nothing,” she tells Jonathan as she leaves with him. “But in my mind is the world as it was. Mine is a better one than the world you live in, Captain. I wish you could see it.” In flashbacks, Jonathan’s father, the late Dr. Stuart Gordon Power, dedicates—and ultimately sacrifices—his life to reversing the unwitting role that he played in the ascent of the machines. Jonathan’s fellow soldier and budding love interest, Jenny “Pilot” Chase (Jessica Steen), spends the entire season reckoning with the deeds that she witnessed and committed as a former member of the sinister Bio-Dread Youth faction. In the devastating final episode, she finally achieves redemption when she bravely takes on a group of Bio-Dread soldiers to protect her newfound team and cause, but it comes at the cost of her own life.

In a 1989 interview with Starlog magazine, DiTillio revealed that additional episodes would have exacerbated those losses for Jonathan, leaving the heartbroken and untethered Captain seeking personal vengeance for Pilot’s death in an even darker second season. But Mattel pulled the plug in early 1988.

There were a number of factors that likely contributed to the show’s demise. At best, the gaming aspect was awkwardly integrated into the rest of the show. At worst, it was a frustratingly futile experience for players at home. The toys sold well below expectations. Given the high cost of making the show, and the blowback that the franchise was receiving from parental groups who found its content too violent, it was no longer a sound investment for the toy manufacturer.

The show also struggled to find its audience. Straczynski blamed the name, which he loathed. “For science fiction fans who were looking for a serious story, they wouldn’t tune into something called Captain Power. And those who would watch a show called Captain Power weren’t often in the mood for a serious science fiction story,” he opines in Out Of The Ashes. Erratic scheduling in many of its syndicated markets played a role, too, leaving intrigued audiences unable to follow or get invested in the dense drama as it unfolded from episode to episode.

It’s also possible that the mature subject matter was an issue for some viewers. The writers’ desire to respect their younger audience was admirable—it’s a demographic that shouldn’t be underestimated—and not without precedent at the time. Comparatively complex villains like Stormer from Jem And The Holograms had introduced the idea of moral relativism to the children of ’80s television, and Optimus Prime’s fall had ushered in an awareness of death and impermanence. The existence of a range of Dune coloring and activity books would suggest that there was at least some market for pint-sized appreciation of weird and dark science fiction. But a show so intensely preoccupied with the weight and ramifications of the past can be a hard sell for a population that doesn’t yet have one of their own.

Of course, it’s also possible that, like so many prematurely canceled shows before and after it, Captain Power was just too much Of The Future to succeed. There’s a decent case to be made for that argument, as the show embraced everything from the act of making sci-fi television in Canada and the (almost) seamless blend of live action and CGI long before anyone else did, and its influence can be seen everywhere from Straczynski’s work on Babylon 5 to the design and ethos of Star Trek’s Borg. Jenny’s death might even have predicted the emotionally gutting character murder that the likes of Joss Whedon and George R.R. Martin have made their hallmark.

That was certainly the angle that Goddard’s new co-producers, Thomas Vitale and Craig Engler, took when the trio announced that they were developing a reboot called Phoenix Rising this July: “Although the surprisingly dark themes, serialized storytelling, and shocking character deaths features within the series were well ahead of their time in 1987, they’re exactly the kind of story elements a modern viewing audience craves.”

Whether or not the entire modern viewing audience is craving Captain Power remains to be seen, but there’s one subset of the population that has definitely caught up to the series: its original young fans. Almost three decades after the show first caught their attention, those children can finally appreciate what it is to have a past that haunts and informs you. When Captain Power returns to television, much like an old war comrade resurfacing in the middle of a mission, they’ll be ready to dig more deeply into its themes—and maybe even do some reflecting on what this rush of nostalgia says about their own lives and where they’re going.

Коментари

Публикуване на коментар